Griffith lab of

Ecology,

Evolution, and

Change

Bridging ecophysiology, evolutionary biology, biogeography, and change.

Monthly Visits

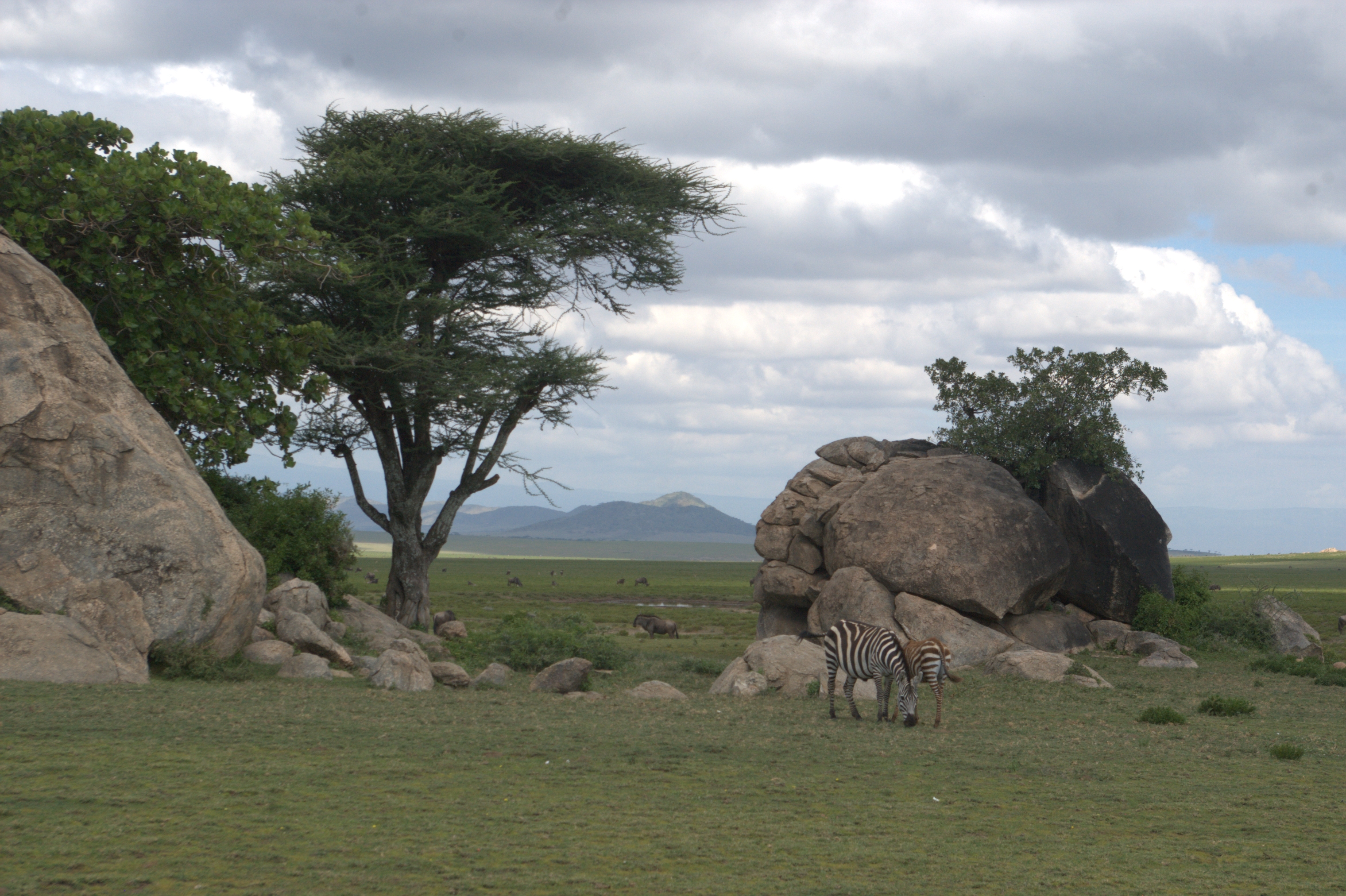

We explore the relationships among plants, climate, and disturbance, with a focus on grassland, savanna, and forest ecosystems. By integrating observations, experiments, ecological modeling, and large-scale data analysis, we aim to unravel how human activities, herbivores, fire regimes, and climate change shape plant communities and biodiversity.

A key focus of our research is understanding how environmental change shapes the function and distribution of traits, individual plants, species, and ecosystems. By bridging ecophysiology with community ecology and macroecology, we contribute to improvement of Earth System Models (ESMs) by incorporating the diverse evolutionary and physiological strategies of plants. My goal is to enhance predictions of ecosystem change under future climate scenarios and inform sustainable land management practices, especially in human-altered environments.

Our research integrates a wide array of cutting-edge techniques, including field-based ecophysiological measurements, drone and satellite remote sensing, thermal and hyperspectral imaging, and ecological modeling. We use tools such as gas exchange systems, stable isotope analysis, and structural equation modeling to investigate plant functional traits and ecosystem dynamics. Additionally, we develop and apply species distribution models and phylogenetic statistical approaches to understand plant community patterns across spatial and temporal scales. This combination of labwork, fieldwork, remote sensing, and computational modeling enables our work to address complex ecological questions about biodiversity, ecosystem function, and the impacts of environmental change.

I strive to cultivate an inclusive and collaborative research environment.